How Nepali Cuisine uses Salt, Fat, Acid and Heat

Episode 5 (last one) – How Salt, Fat, Acid and Heat Make Momo and Choila Delicious

Food represents Nepal's culture, tradition and practices based on geographical regions or ethnicity. Cooking is not all about food; it is a culture and tradition that brings together family, community, society and nation. In the globalized world and with internet connectivity, food is not limited to a particular geographical area and culture. It is beyond borders, and it is science, too. You can find "Dal Bhat" in the busy streets of Paris, "Momo" in Jackson Heights and "Choila" in the corners of London Street.

I started cooking in childhood, primarily to support my mother. Most of our favourite dishes come from our mother's recipe. Over time, I learned many cooking styles and experimented with fusion food from different cultures and traditions. While exploring culinary practices, as a science student, I decided to explore how the science of food influences Nepali cuisine.

Therefore, this article covers how salt, fat, acid, and heat influence Nepali cuisine and their linkages to culture and practices. The article is based on the book "Salt, Fat, Acid and Heat[i]" by Samin Nosrat. I want to share how these elements influence Nepali cuisines and food cultures. I will cite some examples from Nepali cuisines like Khas, Tibetan-influenced, Thakali, Newari, Limbu, Terai, or Tharu.

The article will have five sections. Each will cover salt, heat, acid, and fat, and the last one will explain how these elements make Nepal's two most famous dishes delicious. It’s time to see how Momo and Choila use SALT, FAT, ACID and HEAT.

How Salt, Fat, Acid and Heat Make Momo and Choila Delicious

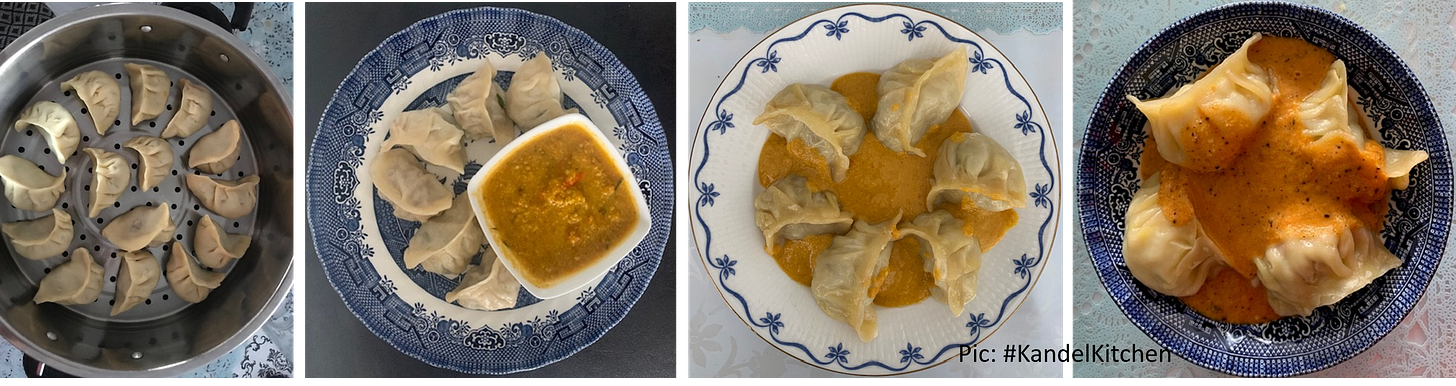

Momo (Nepali Dumplings): It is often said that the Chinese invented dumplings, the Tibetans refined them, and the Nepalese perfected them. This might be due to the perfect harmony of salt, fat, acid, and heat, combined with the use of fresh herbs and spices that define the Nepali Momo. The preparation starts with a stuffing made from fatty minced meat—preferably from buffalo or pork. Unlike completely ground meat, the minced texture retains a satisfying bite. If the chosen meat lacks sufficient fat, adding ghee is a traditional and essential step to enhance the richness.

The minced meat is mixed with finely chopped onion, garlic, ginger paste, and fresh coriander, seasoned with Himalayan or ordinary salt. Onion plays a dual role here—it is a natural source of acidity that amplifies the meat’s flavour while releasing juices that make the filling succulent. When the salt interacts with the meat's fat and the onion’s moisture, it creates the distinctive juicy core of a Momo. Additional spices, such as cumin and coriander powder, are often incorporated to enhance the depth of flavour.

The wrapping process is just as necessary. The stuffing is encased in thin dough wrappers, and a touch of ghee in the dough itself elevates the overall taste and texture of the Momo. Once wrapped, the Momo is steamed. Determining the exact cooking time is an art: experienced cooks rely on the feel and appearance. When the steam feels slightly greasy on the palm or the wrappers turn translucent enough to reveal the juices within, the Momo is perfectly cooked.

A unique feature of Momo is its sauce, unlike any other condiment for dumplings worldwide. The key element of this sauce is acidity, achieved through a base of roasted (heat) sesame seeds, cumin and coriander powder, fresh tomato, coriander leaves, and Timur (a Nepali Sichuan pepper). Additional acidic ingredients, such as Lapsi (Nepali hog plum) paste or fresh lemon juice, are often included depending on the tomato's natural tartness. The balance of flavours—nutty, tangy, and slightly spicy—creates a dipping sauce that complements the Momo’s richness and juiciness, making it a culinary masterpiece.

Choila (Nepali Barbecue Meat Salad) thrives on the perfect balance of fat, acid, salt, and heat, each playing a vital role in unlocking its deep, rich flavours and enticing aroma. Traditionally, this delicacy is prepared using buffalo meat grilled over a hay fire, imparting a distinct, smoky essence unique to the dish. While modern adaptations often employ alternatives like firewood, charcoal, or other grilling techniques, the heart and soul of the preparation remain steadfastly preserved.

Rock salt is a key ingredient in Choila's flavour profile, significantly enhancing the dish’s depth and complexity. To elevate its taste even further, consider preparing the dish a day ahead and allowing the flavours to meld overnight, resulting in a more harmonious and robust culinary experience.

Stone-ground roasted tomatoes, combined with garlic, chilli, cumin, and coriander seeds, add intense intensity while tenderising the meat, thanks to the tomatoes' natural acidity. This step not only amplifies the taste but also enhances the texture of the meat, making it even more succulent.

A generous drizzle of heated mustard oil infused with turmeric powder is added just before serving to complete this masterpiece. This final touch fills the dish with an irresistible aroma and a rich, savoury profile, rounding out its flavour with a warm, earthy note. With its carefully balanced elements and thoughtful preparation, Choila is a master taste, a dish that captivates the senses with every bite.

The chapter will close with a selection of popular dishes from various Nepali cuisines that harmonise salt, fat, acid, and heat. While the list is extensive, here are my top recommendations:

Khas Cuisine: Iconic dishes include Dhal Bhat Tarkari and Kheer.

Tibetan-influenced Cuisine: Highlights are Thukpa (noodle soup) and Momo (dumplings).

Thakali Cuisine: Known for its platters featuring Dhal Bhat, an array of vegetables, spicy pickles, and meat.

Newari Cuisine: Famous dishes include Choila, Samay Baji, Chatamari, Yomari, Bara, Sofumicha, and more. Chyang (rice beer) is a standout.

Limbu Cuisine: Popular items include Yamben (reindeer moss), cooked bamboo shoots, bread made from millet or buckwheat, Tomba (millet beer), and Dharani Bangur (a hybrid of pig and wild boar).

Terai Cuisine: Although influenced by Indian flavours, Tharu cuisine stands out with unique dishes like Ghongi (mud-water snails), Dhikri (made from rice flour), and Sidhara (dried fish).

These dishes, representing Nepal’s rich cultural diversity, embody the bold and intricate flavours that define Nepali cuisine. While we use these essential elements—salt, fat, acid, and heat—in our everyday cooking, we often overlook how much they influence the taste and depth of our food. Many might emphasise the importance of spices like turmeric, garlic, ginger, cumin, and coriander. Still, it’s essential to understand that without the harmony of these four elements, even the finest spices may fall short of creating a balanced flavour. The right salt, carefully controlled heat, and thoughtful use of acid and fat are fundamental to achieving the full taste potential of any dish.

For instance, food simmered over low heat often tastes richer than quick-pressure cooking, as the slow fire allows flavours to deepen and meld. Small details, like adding a drop of mustard oil to Rayo ko Saag (mustard greens), impart a unique warmth and savoriness that olive oil can’t replicate. Similarly, adding a slice of tomato to Palungo ko Saag (spinach) or Cauli ko Tarkari (cauliflower curry) introduces just the right acidity, balancing the dish and elevating the natural flavours of the vegetables.

Traditional ingredients like Bire-nun (Himalayan rock salt) in fresh Dhania ko Achar (coriander chutney) bring a subtle complexity that commercial salt lacks, reminding us of the impact that even a tiny change in one element can make. Each of these adjustments, simple yet intentional, illustrates the power of balance in Nepali cooking, where the flavour is crafted through spices and a mindful blend of essential elements passed down through generations.

Please describe how your favourite food combines the elements of salt, fat, acid, and heat to create its unique flavour. Share your experience in the comment box!

The End

To read the entire series, start from Episode 1 - SALT

Some of the images in the article are from Google Images, and I acknowledge all the photographers who have shared them.

[i] Samin Nosrat. (2017). Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat: Mastering the Elements of Good Cooking. Simon & Schuster.